The Korean Empire (1897–1910) emerged in the turbulent late 19th century as a significant, albeit brief, independent monarchy, representing a pivotal moment in Korean History. Declared by Emperor Gojong from the preceding Joseon Dynasty, its establishment marked a desperate and fervent effort to assert national independence and modernize the nation amidst escalating foreign influence from regional and global powers, notably Japan, the Qing Dynasty, and Russia. This period was characterized by Korea's struggle to navigate an increasingly complex and hostile geopolitical landscape, moving away from its long-standing status as a tributary state to China. Following the decisive Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), which saw China's influence wane significantly, Korea found itself increasingly vulnerable to the aggressive expansionist policies of Japan.

Emperor Gojong's proclamation of the Empire on October 12, 1897, at the Wongudan Altar in Seoul, and his adoption of the imperial title, were profound symbolic acts. These actions were intended to elevate Korea's international status from a dependent "kingdom" to a fully independent Sovereign State, equal to other imperial powers like Japan and Russia. This declaration was a direct challenge to the traditional Sino-centric world order that had long defined East Asian diplomacy. It aimed to establish a new identity for Korea on the international stage, shedding the vestiges of subservience and asserting its right to self-determination.

The Empire initiated ambitious modernization programs, collectively known as the Gwangmu Reforms (1897–1907), named after Emperor Gojong's reign era. These reforms were comprehensive, aiming for self-strengthening through a wide array of initiatives. Militarily, efforts were made to create a modern standing army, reorganize the imperial guard, and adopt Western weaponry and training methods, even employing foreign military advisors, to bolster the nation's defenses against external threats. Economically, the reforms sought to develop a modern industrial base, including the establishment of new financial institutions like the Daehan Cheonil Bank, the introduction of a new currency system, and investments in mining, textiles, and other industries. Infrastructure projects were aggressively pursued, leading to the construction of railways (such as the Seoul-Incheon line), telegraph lines, and modern postal services, connecting major cities and facilitating trade and communication. Educational reforms focused on establishing modern Schools that taught Western sciences, languages, and modern curricula, moving away from traditional Confucian education. Additionally, land reform, including cadastral surveys, aimed to modernize land ownership and taxation, increasing state revenue and improving administrative efficiency. These strenuous efforts sought to transform Korea into a modern industrial state, capable of maintaining its independence.

Despite these significant internal reform efforts, the Korean Empire's existence was tragically short-lived, continually undermined by the intense geopolitical competition in the region. The struggle for dominance over the Korean peninsula culminated in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), a conflict fought largely on Korean soil and waters. Japan's decisive victory in this war solidified its hegemonic position in East Asia and its dominance over the Korean peninsula. This victory paved the way for the signing of the infamous Eulsa Treaty in 1905. This treaty, imposed under duress and without Emperor Gojong's consent, effectively stripped Korea of its diplomatic sovereignty, giving Japan control over Korea's foreign relations and establishing it as a Japanese Protectorate. Emperor Gojong's subsequent desperate attempts to appeal to the international community for support, including dispatching a secret envoy to the Hague Convention in 1907, were met with Japanese retaliation. This led to his forced abdication in July 1907, with his son, Sunjong, ascending to the throne as the last Emperor of Korea. The Korean Imperial Army was disbanded shortly thereafter, leading to widespread resistance from "Righteous Armies" (Uibyeong) composed of former soldiers and civilians. Japan's administrative and military control tightened, eroding remaining Korean autonomy and culminating in the complete annexation of Korea by Japan through the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty in August 1910, formally ending the Korean Empire and beginning 35 years of Japanese Colonization.

Symbols and Flags

Imperial Standard

This flag served as the personal standard of the Emperor of the Korean Empire, used throughout its existence from 1897 to 1910. It typically featured a yellow or golden field, symbolizing imperial authority and sovereignty, and a central dragon motif, a traditional symbol of power and good fortune in East Asian monarchies. The use of this specific design underscored the Emperor's elevated status as a sovereign ruler, distinct from the previous monarchical symbols of the Joseon Dynasty.

This flag served as the personal standard of the Emperor of the Korean Empire, used throughout its existence from 1897 to 1910. It typically featured a yellow or golden field, symbolizing imperial authority and sovereignty, and a central dragon motif, a traditional symbol of power and good fortune in East Asian monarchies. The use of this specific design underscored the Emperor's elevated status as a sovereign ruler, distinct from the previous monarchical symbols of the Joseon Dynasty.

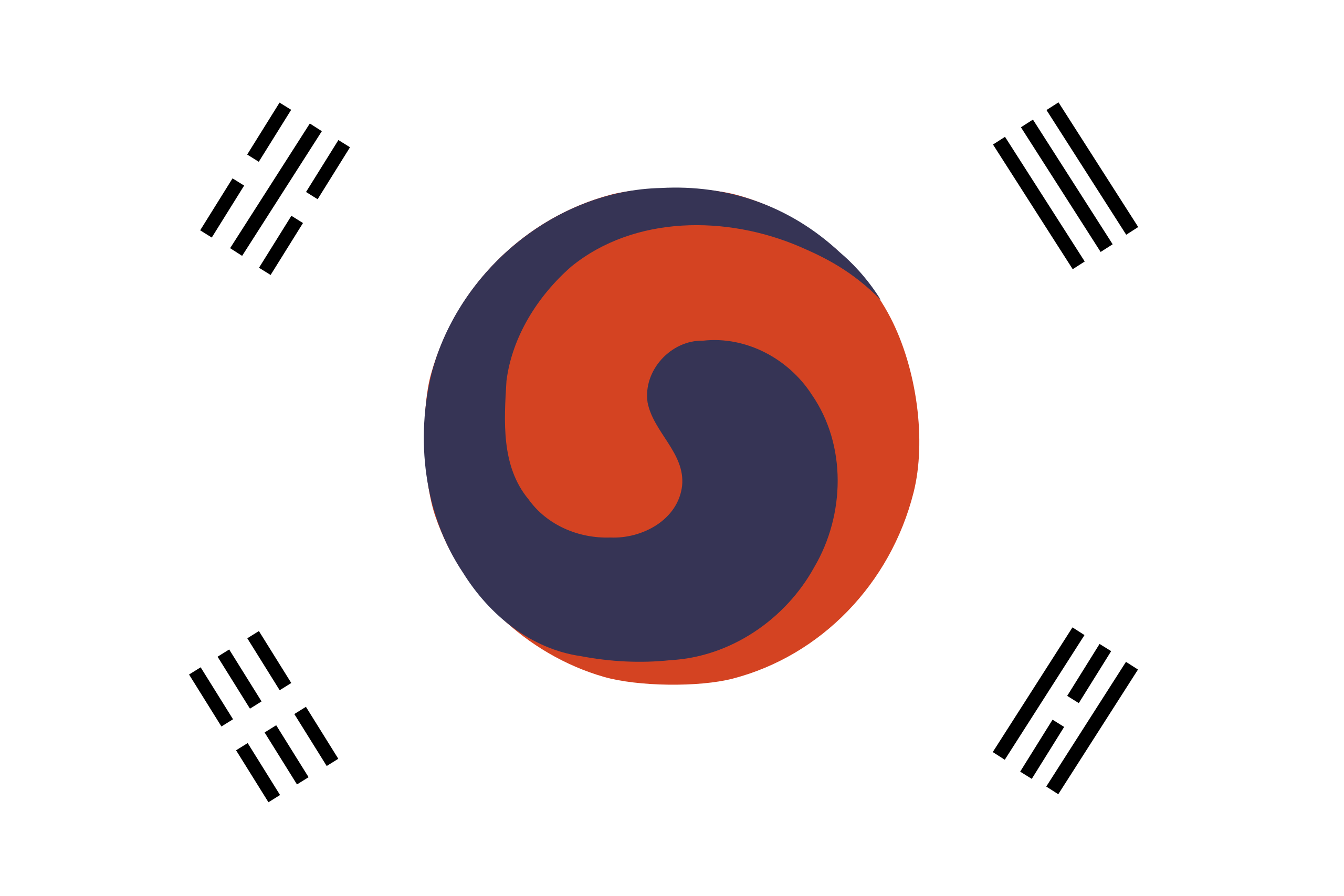

National Flag (1897–1899)

This design was used as the national flag of the Korean Empire during its initial years, from its declaration in 1897 until 1899. It was an evolution of the flag used by the preceding Joseon Kingdom, featuring a white field symbolizing purity and the nation's people, and the central Taegeuk symbol. The Taegeuk, representing the balance of yin and yang, was encircled by four trigrams, each representing a specific element or direction. This early flag maintained continuity with traditional Korean symbolism while asserting the new imperial status.

This design was used as the national flag of the Korean Empire during its initial years, from its declaration in 1897 until 1899. It was an evolution of the flag used by the preceding Joseon Kingdom, featuring a white field symbolizing purity and the nation's people, and the central Taegeuk symbol. The Taegeuk, representing the balance of yin and yang, was encircled by four trigrams, each representing a specific element or direction. This early flag maintained continuity with traditional Korean symbolism while asserting the new imperial status.

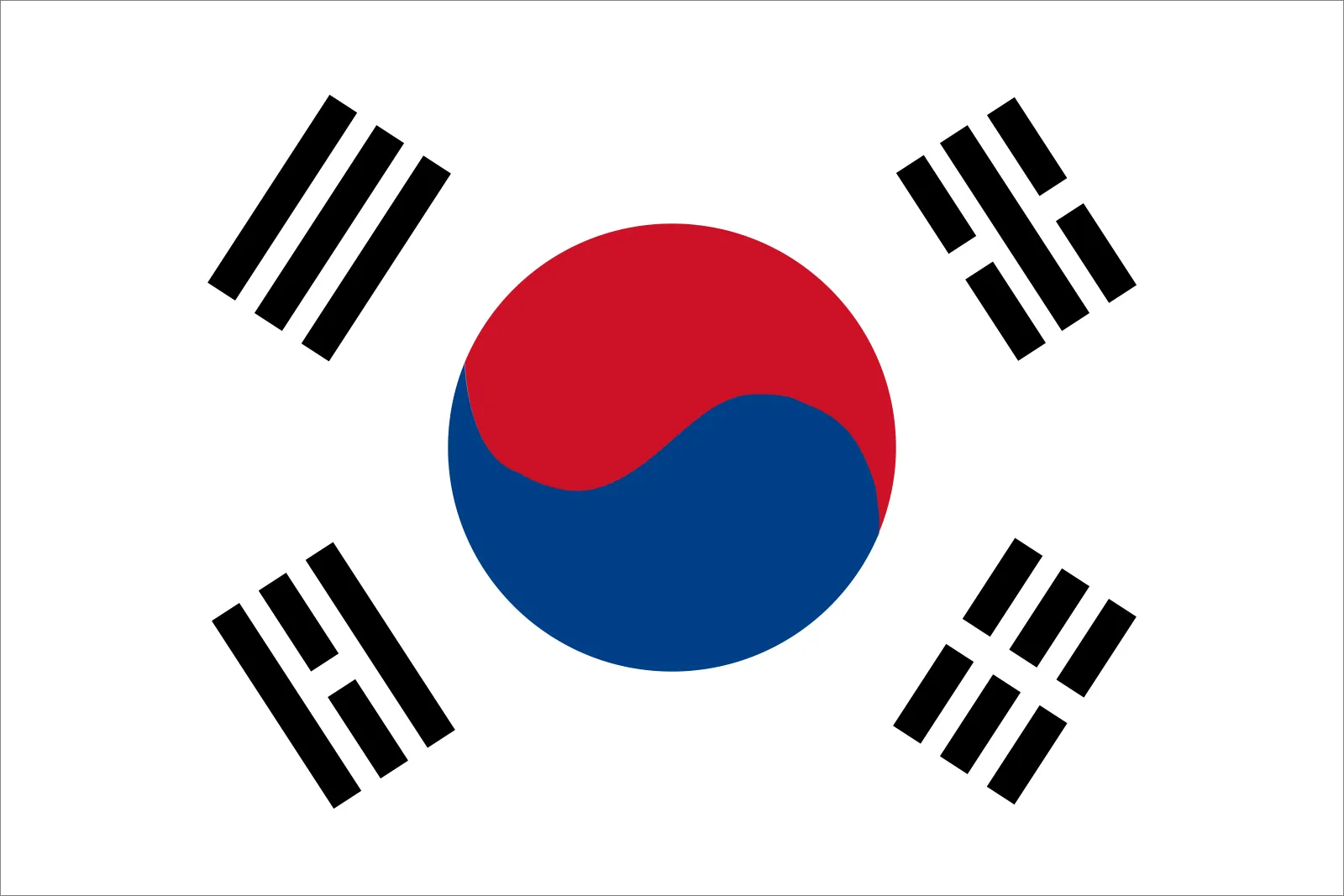

National Flag (1899–1910)

Adopted in 1899, this flag became the official national symbol for the remainder of the Korean Empire's period, until its annexation by Japan in 1910. This iteration of the national flag, famously known as the Taegeukgi, retained the fundamental elements of the earlier design but often featured slight variations in the depiction of the Taegeuk and trigrams. Its widespread use during the Empire's last decade solidified its recognition as the quintessential symbol of independent Korea during a time of immense national crisis and resistance against foreign encroachment.

Adopted in 1899, this flag became the official national symbol for the remainder of the Korean Empire's period, until its annexation by Japan in 1910. This iteration of the national flag, famously known as the Taegeukgi, retained the fundamental elements of the earlier design but often featured slight variations in the depiction of the Taegeuk and trigrams. Its widespread use during the Empire's last decade solidified its recognition as the quintessential symbol of independent Korea during a time of immense national crisis and resistance against foreign encroachment.

Japanese Protectorate Flag (1905–1910)

Following the Eulsa Treaty of 1905, which established Korea as a Japanese Protectorate, this flag was sometimes used to symbolize the growing Japanese administrative and military influence over the Korean peninsula. It featured the Japanese national flag (Hinode, or sun disk) in the canton on a blue field, which typically represented the Japanese-controlled administrative authority, such as the Resident-General's office. This flag represented the era of diminished Korean sovereignty, where internal affairs and foreign relations were increasingly dictated by Japan, preceding the full annexation in 1910. Its visual composition clearly depicted the subordinate status of Korea under Japanese influence.

Following the Eulsa Treaty of 1905, which established Korea as a Japanese Protectorate, this flag was sometimes used to symbolize the growing Japanese administrative and military influence over the Korean peninsula. It featured the Japanese national flag (Hinode, or sun disk) in the canton on a blue field, which typically represented the Japanese-controlled administrative authority, such as the Resident-General's office. This flag represented the era of diminished Korean sovereignty, where internal affairs and foreign relations were increasingly dictated by Japan, preceding the full annexation in 1910. Its visual composition clearly depicted the subordinate status of Korea under Japanese influence.

Culture and Society

During the Korean Empire's push for modernization, significant societal changes began to take root, particularly in urban centers like Seoul. The influx of Western ideas and technologies profoundly influenced various aspects of daily life, leading to the establishment of modern Schools (both secular and mission-run), hospitals, and newspapers. The first electric streetlights and streetcars were introduced in Seoul, symbolizing a rapid transformation from a traditionally agrarian society to one embracing industrial advancements. Traditional social structures, deeply entrenched during the Joseon Dynasty, began to slowly erode, with calls for an end to social hierarchies and the promotion of individual rights, though the majority of the population in rural areas continued to live much as they had for centuries.

Intellectuals and reformers, often influenced by Western education or experiences abroad, advocated for sweeping changes to strengthen the nation. The growth of independent newspapers like The Independent (Dongnip Sinmun) played a crucial role in shaping public opinion and fostering a sense of national identity and civic engagement. Cultural movements also emerged, blending traditional Korean aesthetics with new influences, especially in Art, literature, and architecture, reflecting the nation's struggle for identity amidst rapid change and foreign pressure. The emphasis on education led to increased literacy and a burgeoning intellectual class, which became instrumental in articulating the nation's plight and resistance against Japanese encroachment. Despite the rapid changes, traditional Confucian values continued to hold sway in many aspects of society, creating a dynamic tension between old and new.

Legacy and Modern Korea

The Korean Empire's brief but impactful existence laid foundational elements that profoundly influenced the development of modern Korea. While the Empire itself was annexed and ceased to exist as a sovereign entity, its pursuit of independence and modernization, particularly through the Gwangmu Reforms, continued to resonate through the subsequent colonial period and the eventual establishment of independent Korean states. The ideals of national self-strengthening and sovereignty, fiercely championed by Emperor Gojong and his government, became cornerstones of subsequent Korean nationalist movements. The infrastructure, educational institutions, and economic foundations laid during this period, though often exploited by the colonial power, provided a crucial starting point for later nation-building efforts.

Following WW2 and the liberation from Japanese rule, the Korean peninsula was tragically divided into North Korea and South Korea. Despite their ideological differences, both states drew upon the historical narratives of the Korean Empire's struggle for independence and modernization as part of their national identity. In South Korea, figures like Emperor Gojong are often remembered as patriotic leaders who bravely resisted foreign domination. The legacy of Korean national identity, in part forged during periods like the Empire's desperate fight for survival, continued to evolve within these new states, shaping their respective political cultures, historical narratives, and aspirations for national unity. The era of the Korean Empire, therefore, remains a critical chapter in the ongoing narrative of Korean History, demonstrating the enduring spirit of the Korean people in the face of immense adversity.

Flag of South Korea

This flag, the Taegeukgi, represents modern South Korea. While distinct from the historical flags of the Korean Empire in its precise design and proportions, its central 'Taegeuk' symbol and the four trigrams bear a direct and strong resemblance to the principles and aesthetics found in earlier Korean national symbols, particularly the national flags used during the Korean Empire period. This continuity reflects a deliberate connection to a long heritage of Korean national identity through different eras of Korean History, symbolizing unity, balance, and the aspirations for national prosperity and independence.

This flag, the Taegeukgi, represents modern South Korea. While distinct from the historical flags of the Korean Empire in its precise design and proportions, its central 'Taegeuk' symbol and the four trigrams bear a direct and strong resemblance to the principles and aesthetics found in earlier Korean national symbols, particularly the national flags used during the Korean Empire period. This continuity reflects a deliberate connection to a long heritage of Korean national identity through different eras of Korean History, symbolizing unity, balance, and the aspirations for national prosperity and independence.

Flag of North Korea

This flag represents modern North Korea. Adopted after the division of the Korean peninsula, its design features a wide red central stripe with blue stripes above and below, separated by thin white lines. A red five-pointed star within a white circle is situated on the hoist side. This flag reflects the distinct national identity established for the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, emphasizing its revolutionary and socialist ideology. While it visually contrasts with the historical symbols of the Korean Empire and the flag of South Korea, it remains a key symbol in contemporary Korean History, representing a unique path of national development and identity in the post-colonial era.

This flag represents modern North Korea. Adopted after the division of the Korean peninsula, its design features a wide red central stripe with blue stripes above and below, separated by thin white lines. A red five-pointed star within a white circle is situated on the hoist side. This flag reflects the distinct national identity established for the Democratic People's Republic of Korea, emphasizing its revolutionary and socialist ideology. While it visually contrasts with the historical symbols of the Korean Empire and the flag of South Korea, it remains a key symbol in contemporary Korean History, representing a unique path of national development and identity in the post-colonial era.

See also

Want more? For related content, explore WW2.

Want more? For related content, explore WW2.